Oceanic: International Melville Conference UConn Avery Point

Flare into being.

“This project began for me in the Reading Room of the Houghton Library at Harvard University in 1984 when I had some extra time on a rainy afternoon after examining the art books…”

melvillesprintcollection.org/items/show/192.

#MelvilleMonday

— Moo Dog Press (@moodogpress.com) March 31, 2025 at 10:30 AM

Melville and the ocean. A reader writes. A writer reads.

“…there will be a number of special events and a Melville-related field trip to Mystic Seaport Museum, including touring the 1841 whaleship Charles W. Morgan. We are also planning an optional post-conference day-trip to New Bedford…”

www.melvillesociety.org/conferences

#MelvilleMonday

— Moo Dog Press (@moodogpress.com) March 17, 2025 at 9:23 AM

Tried to read Moby-Dick as a pre-teen. A paperback copy with Ahab and harpoon and the white whale on the cover was stored in my older sister's desk–a small book and so alluring. Opened and tried to read it, but the understanding proved to be more than a challenge. Put it back. Decades later, a portal opened and reading the same book (a different version, but unabridged of course) transported with words to a new land of wonders and humor, knowledge and horizons.

In June, an international conference Oceanic Melville. Register by June 6, 2025 (11:59 p.m.).

From the official site:

“Herman Melville (1819-1891) closely observed oceanic life and death from the decks of ships and found a ‘nervous lofty' language with which to engage its beauties and terrors. He has inspired many a reader to go to sea, imaginatively or otherwise. But how does one think about Melville’s Ocean in the 21st century? What has happened to the romance of the sea—to his ‘renegades and castaways,' the Handsome Sailor, or Pacific, Indigenous, African, or Lascar mariner? What has become of the ‘watery part of the world' that both separates and connects the continents?

“In the Anthropocene, one might say that the romantic ship-narrative has sailed, replaced with a clearer understanding of the human impact on marine climate and environmental stability and the human pressure on beings who live in or depend on the sea. Within a variety of contexts, then—ecocritical, aesthetic, ethical, sociopolitical, posthuman—how do we read and return to Melville’s oceanic texts and themes?

“The Fourteenth International Melville Conference, Oceanic Melville, will investigate these questions and others within a broad understanding of the term ‘oceanic.'”

The Oceanic Melville conference will be held on the maritime campus of the University of Connecticut at Avery Point in Groton, Connecticut, June 16-19, 2025.

“The first International Melville Conference was held in Volos, Greece, in 1997. Since then, there have been twelve more, held in Mystic, CT (1999), Long Island, NY (2001), Lahaina, Maui (2003), New Bedford, MA (2005), Szczecin, Poland (2007), Jerusalem (2009), Rome, Italy (2011), Washington, DC (2013), Tokyo, Japan (2015), London, England (2017), New York City (2019), and Paris, France (2022). Oceanic Melville will be the fourteenth.”

Conference Organizing Committee: Mary K. Bercaw Edwards, University of Connecticut. Wyn Kelley, Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Tony McGowan, United States Military Academy.

After learning about this event, recalled a walk a few years back around the beautiful University of Connecticut campus that is Avery Point.

Stepping away from the Connecticut River valley and beloved basalt ancient hills a few years ago meant not going far. (Far is a word that means something different depending on where you live or have lived. In Florida and Virginia, an hour's drive to get groceries and visit the library was something normal. In Connecticut an hour will take you to other states.)

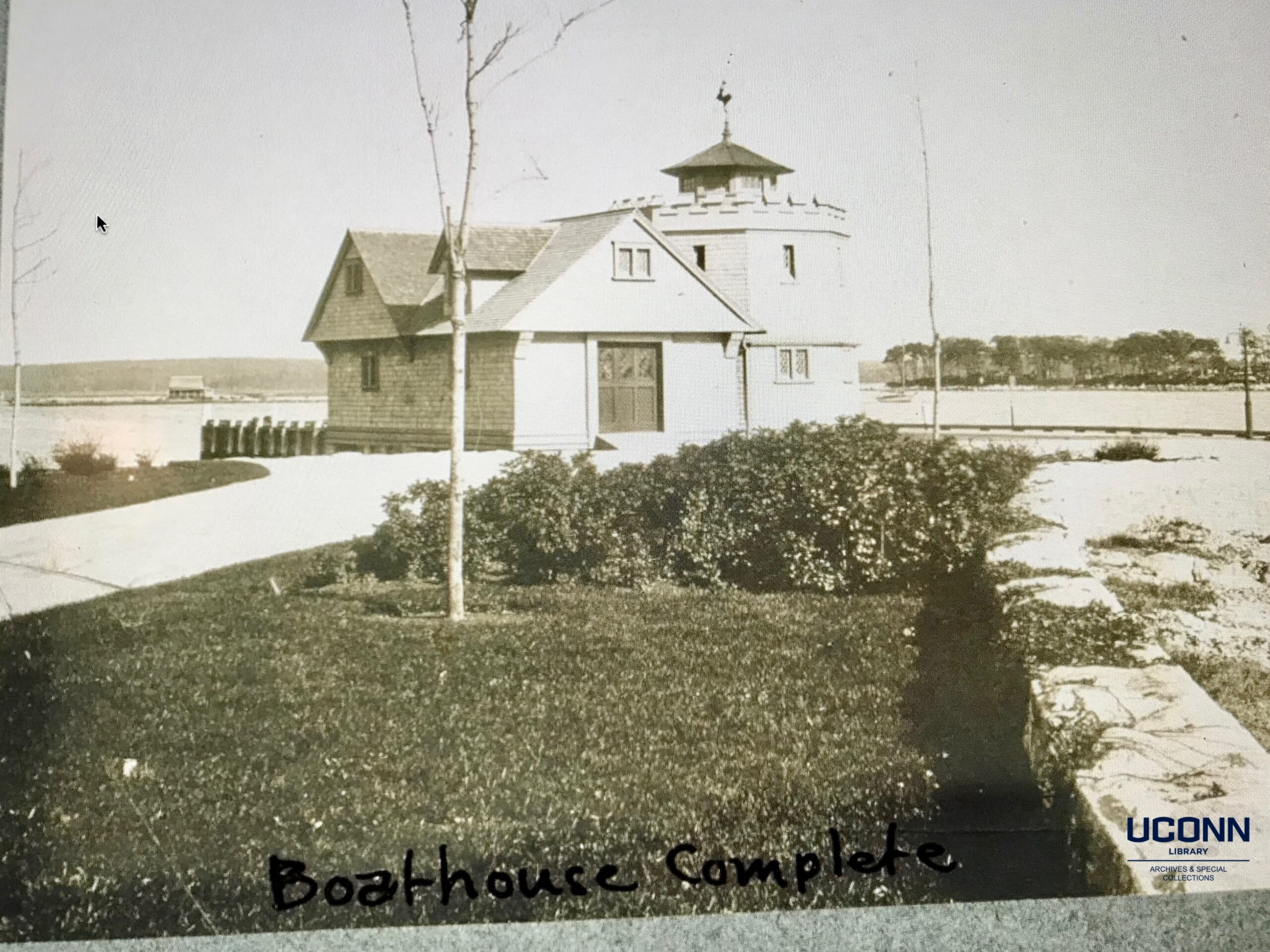

And there was the lure of water, the scent of ocean and Long Island Sound sounds. Bell buoy rocking with the wake of boats, seagulls, distant conversations, slapping of waves on breakwater. Wrack lines along the shore, seaweed and shells. People fishing. Sailboats on the horizon. Dog walkers, only two; and a solo walker. A structure that provoked curiosity. Almost looked like a wooden castle. What is it? What was it?

During construction, 1903. Laborers complete roof on tower of boathouse. Man on scaffold works on shingles of main portion of boathouse. Others working at base of tower to complete exterior. UConn Library Archives.

Then. Is it still there now? Time flows and carries much away, burnishes all as it flows, takes and gives.

Avery Point history. Shennecossett Road (now there's a word/place name worth learning about) and finding more.

"Melville, like Ishmael, 'swam through libraries and sailed through oceans' in pursuit of the whale. His shipmates, like those of Ishmael, came from all the 'isles and ends of the earth.'

"…artwork… on loan from the Melville Society Archive."

Event: uconnuecs.cventevents.com/event/Melvil…

— Moo Dog Press (@moodogpress.com) March 31, 2025 at 1:56 PM

Seeing that quote in stone on an Avery Point bench sparked thoughts of meeting Stephen Jones and touring Schooner Wharf and tugboat, Anne, for a story about the history of another building in Mystic — the former Lathrop Marine Engine complex on Holmes Street.

Related story via Town Dock (NC 2015) linked here.

Jones, a multi-dimensional human — emeritus “Professor of English and Maritime Studies. Avery Point. Chair, Maritime Studies Curriculum Research specialties: Fiction and nonfiction literature of the sea; American nature writing; Shakespeare; short story; modern British novel; journalism.” That's from his official page, which includes a link to his books. So add publisher, founder, author, historian, and lively storyteller of people, places, regions. Here's another story link that includes him as co-author of a book about the Connecticut River, ferries. Following him on a tour of the building that houses Mystic River Yarns, offices, a restaurant, bookbinder, meant seeing hidden features and back passages, vintage photographs.

In the region is the Whale Tail fountain in New London, Connecticut. New London, of course, was a whaling port and is still known as the Whaling City. Visitors may also choose to step inside the Custom House Maritime Museum on Bank Street for more area histories linked to the world. A tour fee is charged but perusing the gift shop is free.

Also notice the indigenous words throughout this region.

Such as “Noank; village in New London County, Connecticut. Derived from the Indian word, naytmg, ‘point of land.' — page 225, Bulletin No. 268 Series P, Geography, 45, Department of the Interior United States Geological Survey. Charles D. Walcott, Director. The Origin of Certain Place Names in the United States (Second Edition) BY Henry Gannett Washington (Government Printing Office 1905).

“You've done it before and you can do it now. See the positive possibilities. Redirect the substantial energy of your frustration and turn it into positive, effective, unstoppable determination.” Ralph Marston

The history of the buildings, people, gardens, connections and context–a great read before or after a visit to UConn Avery Point.

Note: A portion of this story was previously published during the pandemic. A valuable and insightful book to read before a visit to the Avery Point campus is Morton F. Plant and the Connecticut Shoreline: Philanthropy in the Gilded Age by Gail B. MacDonald (History Press 2017)–buildings and landscape, context of what once was here and buildings that remain. This story has been updated