Dorrie In The Quarry: Fabled Strickland’s (Garnets!) What Used To Be

“The rock I'd seen in my life looked dull because in all ignorance I'd never thought to knock it open. People have cracked ordinary New England pegmatite – big, coarse granite – and laid bare clusters of red garnets, or topaz crystals, chrysoberyl, spodumene, emerald. They held in their hands crystals that had hung in a hole in the dark for a billion years unseen.” Annie Dillard, An American Childhood

Run away with me.

Decision made (as a child), my mother calmly packed me a sandwich and tied a red bandana (your father's hanky) around the chow, then tied it on a long stick, and said “go ahead.”

Nowadays, this would be verboten.

But out the door and into the back field, where the woods stood. Sat down. Sat. Ate the sandwich. Cooled off, thought. And eventually returned to the house. A gift, being born to this woman, her man.

The other default was animals, Enraged as a child, going out to the portable (a former beach camping house now retired), and into the dog nest box under the bench to ugly cry. A dog would arrive to be hugged and fur gripped. Sobs absorbed, patient creature. The world was so confusing and so not fair. (Who told you the world was going to be fair, mom would say.)

Stop. Go. Stop. Pay attention. Go for a walk. Work. Sleep. Eat. Wonder.

Amid the current chaos there is great comfort in red-winged blackbirds, greening fields, spring ephemerals. Walks with a beloved canine companion. Kick, kick, kick–she provokes laughter. Reminds that what we have is more than plenty–time. Ability to walk, read, think, pay bills. The right now.

Treasures may be found by many methods. And define treasure–first, as that's a personal choice. Stories are collected because otherwise the words may be lost. Regular people and their lives. Hard work, dedication, helping and trying. We all are not here long. (Ask me how I know.) This is a story written because a middle school student (she's an artist) adapted a cover and then shared the illustration. Decades after the report was handed in. One sister is gone; one still here.

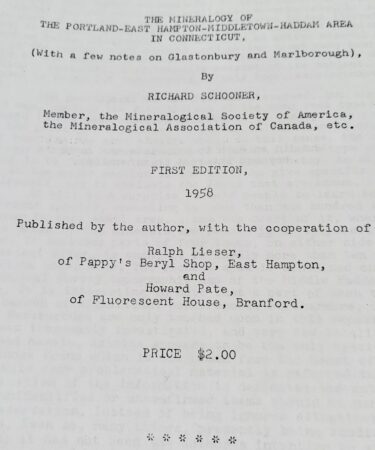

Traced cover, original booklet is by Richard Schooner (1958) The Mineralogy of the Portland-East Hampton-Middletown-Haddam Area in Connecticut with a few notes on Glastonbury and Marlborough. Which she has kept, another treasure.

Courtesy of Dorrie Marino, she said the cover was traced for a report decades back as a student in Washington Middle School (formerly Meriden High School) in Meriden, CT.

Here is the original attribution. Also see Mindat.

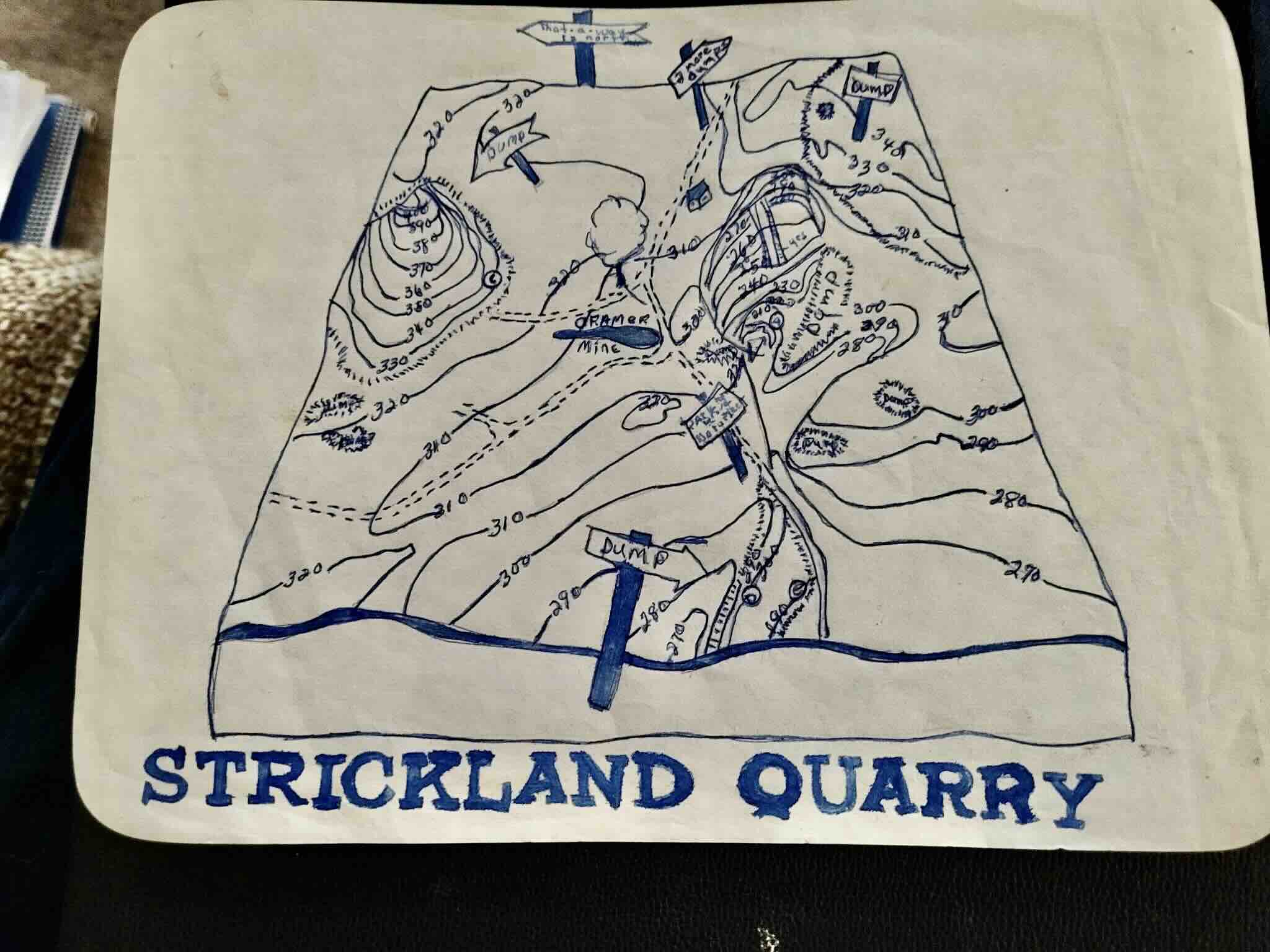

Zoom in to look; quarries–many no longer accessible–and the wonders of minerals collected. At New Haven Mineral Club's recent show. (Asked permission to take images; courtesy as this is a club event. Open to the public, who were enthusiastic and buying plenty.)

At the recent New Haven Mineral Club show in North Haven (easy to get to, plenty of parking), the array of displays were incredible. People, nice. Engagement with the public, A-plus.

Strickland's. Gone, but not ever forgotten. Pegmatites and “mountains” of tailings from the mine. Geology absorbed.

My dad had a theory that people in the north moved faster and talked more quickly because of the climate. He was a curious man. As we were traveling across a seemingly endless stretch of Florida Panhandle backroad, he drove across a series of rumble strips intended to alert a driver that a stop and intersection was ahead. During his visit, we shuttled back and forth on that road quite a bit. Then one day he came up with a tune based on the rhythm of those road sounds. Odd. Yet it was a catchy little ditty. Who else could dream up such a thing?

Time was when this was mud. Today it is stone with fossil mudcracks atop a wall where busy life streams past at a busy intersection in a small city on the Connecticut River.

He noticed things most people missed. Also dad enjoyed time with his six offspring and a herd of friends and neighbors in, out, and around our home. In time, that crowd included grandchildren. After he officially retired, he was more productive than ever.

And in the Connecticut River Valley, once you start looking, dinosaur footprints show up everywhere. Fossil mudcracks, tracks with nails visible, scribbles of multi-legged critters in long ago mud flats now hardened to stone and weathered by time. “Most people walk past them” said a librarian at Portland Public Library, a river town that is home of former brownstone quarries that have yielded not only tons of handsome stone for area buildings and in New York City, but also beautifully preserved fossil prints. Near the old quarries, walls often feature traces of prehistoric life – especially clear when the natural light in the late afternoon illuminates them.

Speaking of impressions, Dad once told me that young children have minds like clay. He once demonstrated how easily they pick up all they hear and see. As he worked outdoors in his woodshed/shed/workshop, he sang a catchy tune – seemingly oblivious to the youngster under his care nearby. Sure enough, minutes later the little boy started humming the same tune he had just overheard as he played with toy cars. Dad gave a nod and went back to raking, tinkering, fixing.

#FossilFriday

— Moo Dog Press (@moodogpress.com) April 11, 2025 at 4:52 AM

“The Connecticut River Valley is a geological paradise. Once you learn to read its rocks and landscape, the valley becomes a museum, a 300-mile-long museum of our earth's history,” according to Professor Ed Klekowski of the University of Massachusetts Amherst, who has created an online course on the geology, history and biology of the Connecticut River, which is New England's largest river.

Read more

Conversation. Maybe join both clubs, Meriden Mineral Club and New Haven Mineral Club? (Can I just of along on the field trips and report?)

Editor's note: On the journey: Bloodroot seen, admired, left to grow more. Trillum. Asking around to find trailing arbutus just to inhale the scent. Old golf course bunkers and conversations about coins, finds, places. Melville Monday conference (June) for those who love Melville (and more memories). A visit to listen to Kriz Farm farrier..

New location of Book Barn Downtown, Niantic. Nearby is a Dairy Queen. 🍦

— Moo Dog Press (@moodogpress.com) April 8, 2025 at 8:49 PM