COVID-19 Era: Metacomet, Pequots, Deep Time – Walk Between Worlds

Words and images, actions and ideas can (and do) spark others. A sign is seen and curiosity leads to stopping for an image capture. Then a connection, a book, more books, meeting others who have pieces of a puzzle.

Remembering a note on an old professor's door that read "Eschew obfuscation," in case you're wondering how the writing is going this morning.

— C.B. Bernard (@cbbernard) May 20, 2021

“Metacomet (1638–1676) – also known as Metacom and by his adopted English name “King Philip” – was chief to the Wampanoag people and the second son of the sachem Massasoit. He became a chief in 1662 when his brother Wamsutta (or King Alexander) died….” this is a portion of what will be found online in response to a query about why a Native American sachem would be known as “King Philip.” But there is so much more to this story and his life. First of all, Massasoit is the Wampanoag chief so integral to the story (and survival) of Plymouth Plantation. Then there is controversy as to Mooanam, later called Wamsutta, first son and heir to Massasoit. He was taken by authorities for questioning, then died soon after his release – some think it was murder by poison.

In school, learned history but facets of humanity chosen to appear in textbooks. The resource of a public library provided stacks for independent reading, much. Going out into the world and travel, reading, reading, reading provided so much more. Stanton-Davis Homestead, for example. Cultures meet and layers of history abide. (For more, including a thread about Venture Smith see this link to a page and video in 2012 by William Hosley.

Where cultures meet and stories abound. Stanton-Davis farm and homestead. Story linked to this image from 2018.

Then traveling the region, drives to and from Vermont, upstate New York, Cape Cod, Massachusetts byways and backroads to decompress led to frequent stops to investigate place names, signage, history on site. All added to knowledge, distilled into writing while founding one publication, taking it digital. Working remote in 2009 collaborating with designers and teams far and near. What is possible? Still learning. Mattabasset is a name of a condo community, a trail nearby beloved since childhood. But the word goes much farther back into time.

As all connects, ebbs and flows a noteworthy event via Avon Public Library: Connecticut Native American Communities Past and Present – presented by Dr. Lucianne Lavin, Director of Research and Collections, Institute of American Indian Studies, Washington, CT. Lavin is author of Connecticut's Indigenous People. What Archaeology, History and Oral Traditions Teach Us About Their Communities and Cultures, Yale University (2013). She will explain how these indigenous communities were the first environmental stewards, astronomers, mathematicians, zoologists, botanists and geologists. In reality these “pre-contact” tribes have been, and still are here, for more than 10,000 years. Registration is required; free. Thursday, Sept. 9, 7 p.m. Link to a listing via Patch, here.

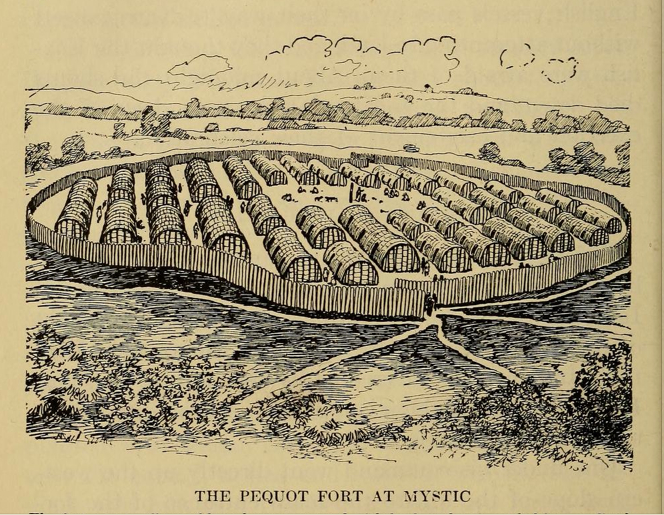

Learn more about battles between cultures. Image is linked to Pequot War Battlefields site for research and updates.

“Before the Pequot War (1636-1637), Pequot territory was approximately 250 square miles in southeastern Connecticut. Today, this area includes the towns of Groton, Ledyard, Stonington, North Stonington and southern parts of Preston and Griswold. The Thames and Pawcatuck Rivers formed the western and eastern boundaries, Long Island Sound the southern boundary and Preston and Griswold (southern parts) the northern boundary. Some historic sources suggest that Pequot territory extended four to five miles east of the Pawcatuck River to an area called Weekapaug in Charlestown, Rhode Island prior to the Pequot War.

“Within this territory during the early 17th century lived some 8,000 Pequot men, women and children (4,000 after the smallpox epidemics of 1633-1634), residing in 15-20 villages of between 50 to 400 people before the war. These villages were located along the estuaries of the Thames, Mystic and Pawcatuck Rivers and along Long Island Sound.” — The History of the Pequot War

Powerful story about the meeting of two cultures, an interactive traveling exhibit. Image from “Our Story” is linked to official site.

Battlefields of the Pequot War Project image, linked to official site for more information. The purpose of some objects found remains unknown.

Repeating from another story, this excerpt about the early history of the Glastonbury-Rocky Hill Ferry Historic District, Hartford County, CT (NPS):

“Even though proprietors made use of their land on the east side of the river, the general reluctance to permanently settle in such a relatively isolated wilderness was understandable. Fresh in their memories was the 1637 massacre of nine Wethersfield settlers, the major proximate cause of the retaliatory Pequot War. Even though they grazed their cattle in the meadows and grew hill corn in the Native-American manner in the fields there, most farmers crossed the river every day to look after their farms. A few hired cattle herders, who lived in temporary quarters, or like John Hollister, employed someone to take care of their property. Settlement was delayed further by another period of unrest later in the century that culminated in King Philip's War (1665-1667), a last ditch effort to drive Europeans out of New England, in which towns were burned and their inhabitants massacred.”

Real history. And with more than 10,000 years of human history on land and waterways known today as Connecticut – some lives left traces; many did not. Many stories wait to be told. New combinations of technology help find them and may aid in telling narratives in novel ways.

For added insight, read King Philip's War: The History and Legacy of America's Forgotten Conflict by Eric B. Schultz and Michael J. Tougias. The truth of King Philip – and horror of what happened to him – including grisly details after death – unforgettable.

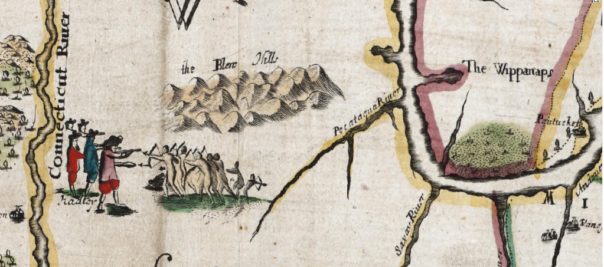

Detail of an ArcGIS map of King Philips War. Hadley is the town name written that shows under the shoes of the people to the left, but the sketch is also a visual commentary of the thoughts of the map maker. Colonists are shown in vivid color to the left; indigenous people – fighting for their lands – are depicted in pen strokes to the right. Image linked to ArcGIS map – high resolution and zoomable for seeing fine detail.

There is also research for evidence from the conflict by Mashantucket Pequot Museum including much work by Project Director Kevin McBride, who has teamed up with students from the UConn Archaeological Field School as well as with private citizens in targeted communities to find traces and artifacts by excavating or using ground penetrating radar and other technologies. The Denison Homestead was one such dig to locate a possible stockade and other protective features built during King Philip's War, 1675 to 1676. Dave Naumec, military historian, senior researcher, archeologist, at the Mashantucket Pequot Museum, is part of the project team.

Professional technical help is a call away about documenting a site and what to do about finds – even if the land is being developed (the information tied to place is what will be collected and help beyond that if necessary). Here is an excerpt Q&A of the Museum of Natural History/Connecticut Archaeology Center, the official state repository for archaeological artifacts from Connecticut and is interested in pre-historic and historic materials that will increase understanding of the past.

What can I do to protect archaeological resources located on my property? Good stewardship begins with responsible actions. Native American sites can be very old, very fragile, and offer significant insights about the distant past. If you discover Native American artifacts, contact the Office of State Archaeology for appropriate guidance.

If you occasionally find broken bits of early ceramics or other Colonial-era artifacts while gardening or landscaping, develop a system for recording or cataloging where these discoveries occurred. Draw a map of your property and describe where and how each find was discovered. This information will help future property owners, historians and archaeologists better understand the property's changing history and use through time. However, if you discover a buried foundation or a dense concentration of historic artifacts on your property, seek the professional assistance of the Office of State Archaeology. The information of how objects are found in relation to each other may unlock more knowledge.

Where can I donate my collection of artifacts? If you have materials you think might benefit this effort, and are looking for a safe, permanent home for them, contact the museum for options. Here is the link.

How can I learn more about the history of my property? Many resources exist for owners of older houses. Archival research will provide a better understanding of your house and lands. For instance, your local library, town hall, and historical society can often provide important information about the land use history of the property. A title search, old maps and atlases, tax records, government census records, and town histories may offer insights about former owners, their families and their occupations, as well as information on other structures that may have once existed on the property. Municipal historians are also highly knowledgeable and are eager to assist with research about their communities.

“Archaeologists have uncovered evidence of humans living in Southern New England as far back as 11,000 years ago, coming here right after the last glaciers melted away.”

“We have found stone tools, food middens, human remains, Colonial building foundations, the hulking remains of old industrial mills – and a host of other objects. True scientific analysis reveals a complex story about people's changing relationship to the place they live. People seemed to have a more direct relationship with the world around them than we do today. . . . in the 21st century it almost seems like we live outside of nature. In this exhibit we explore the natural history of southern New England, how it shaped and continues to shape the lives of people who live here, and how we, in turn, have reshaped the environment,” says Emeritus State Archaeologist Nick Bellantoni in a video that is part of interactive story stations at Human's Nature at The Connecticut State Museum of Natural History & Connecticut Archaeology Center, part of the University of Connecticut College of Liberal Arts and Sciences. Visitors are invited to digitally “meet” scientists, educators and historians who reveal what their work in geology, climatology, conservation biology, ethnobotany, and archaeology reveal about the way we live today.

This. This is what was found after walking, hiking, getting lost and found while research for a revision of Short Nature Walks Connecticut, a slim volume in many editions since collected when spotted. The late Eugene Keyarts penned the original. It was an honor to follow in his footsteps and in the work of the previous revision author Carolyn Battista.

Editor's note: The quote under the first image is the late (great) Ossie Davis as “Marshall” from Joe versus the Volcano a movie that is a parable of sorts. Here's another line of dialogue: “Patricia: My father says almost the whole world's asleep. Everybody you know, everybody you see, everybody you talk to. He says only a few people are awake. And they live in a state of constant, total amazement.”

The late Whit Davis riding Blaze. From a tribute. Stonington Land Trust official site linked to this image for updates and announcements about walks open to the public.

Portions of this story were previously published as the journey to understand, unearth, read and connect events from the past with the present continues while writing chapters of it as all unfolds. An update was made on June 7, 2021. And although fully vaccinated, will continue to wear a mask and listen to best practices and health precautions to protect others while tentatively re-emerging during a global pandemic. First non-essential visit? A bookstore where all wore masks and the entrance door was left open for ventilation. Many children are not yet vaccination and much of the world still waits for this vital protection. As all continues to shift, visit our Resources page at this link. Many events not yet listed, decisions still to be made.