River Ride Into History: Dutch Point Archives, The Onrust

“…his journal of that voyage has specific observations on the River's depths, its navigation and on the Native Americans. He was gathering information for Amsterdam merchants on the potential of the fur trade and had made at least two previous voyages to the New World.”

Editor's note: This story has been added to and moved to here.

Looking at bald eagles along the Connecticut River from the Onrust in full sail. (Left) Jim Byron, deckhand, helps guests spot eagles.

And yes, there was conflict, competition, cooperation. After his first boat burned (or was set afire?) “…Block stayed through the winter near Manhattan Island. They built some primitive huts on the island, which were the first western settlements of what later became New York City. They managed to build a new ship, named the Onrust (‘Restless’; the translation ‘Troubles’ is rather unlikely) with help from the Native Americans.” — Wracklines magazine (Connecticut Sea Grant/UConn) feature story by Johan Cornelis Varekamp and Daphne Sasha Varekamp (professor Earth and Environmental Sciences, Wesleyan University, and his daughter, respectively).

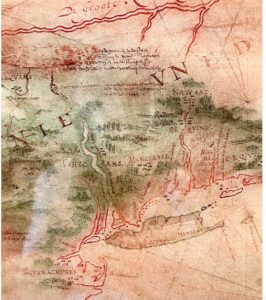

“Cornelis Rijser, successfully returned in the St. Pieter in 1611, and Block and his fellow captain Hendrick Christiaensen returned the next year in 1612, bringing back furs and two sons of a native sachem in the Fortuyn and another ship outfitted by a group of Lutheran merchants. It took about ten weeks to sail to New Netherland, sometimes longer. The prospect of successful fur trade prompted the States General, the governing body of the Dutch Republic, to issue a statement on March 27, 1614, stipulating that the discoverers of new countries, harbors, and passages would be given an exclusive patent good for four voyages undertaken within three years to the territories discovered, if the applicant should submit a detailed report within 14 days after his return.”

So. Block is not only an explorer, but also a businessman, venture capitalist, cartographer, observer and writer. Captain of his ship of life, so to speak. But what nerve and ability combined to stay alive, manage his crew and ship, navigate the voyages. No guarantees of success, but what if he could capture the data and return, establish contacts and also open up new avenues of revenue?