Creative Region: The Fiber Festival of New England Weekend

Create: 1. To cause to come into being, as something unique that would not naturally evolve or that is not made by ordinary processes. 2. To evolve from one's own thought or imagination, as a work of art or an invention. 3. Theater. To perform (a role) for the first time or in the first production of a play. 4. To make by investing with new rank or by designating; constitute; appoint: to create a peer. 5. To be the cause or occasion of; give rise to… 6. To cause to happen; bring about; arrange, as by intention or design… 7. To do something creative or constructive. – Dictionary.com

Where does creativity come from? Encourage it to grow, learn by doing at The Fiber Festival of New England.

The Fiber Festival of New England is a two-day market focused on creativity and production of natural fibers for an entire region on Saturday, Nov. 4 and Sunday, Nov. 5, inside the Mallary Complex at Eastern States Exposition, West Springfield, Mass. Micro enterprises, small farms, business. The mission to “promote the use of wool and other natural fibers and related products to the general public.” Artisans, craft, supplies. Human ingenuity expressed in traditional processes – and some brand-new techniques. Workshops (some already full they are so popular) offer opportunities to try a new medium, learn another skill.

While walking around and looking at the output of what human make for their own enjoyment, to sell, or to just to exhibit, consider this: Making things, design thinking, creative work – all feed into what makes a place unique. Creativity is an economic force to the overall economy of a region – and for the nation.

More than 150 exhibitors gather to showcase what they make – yarn, fiber, designs, charts, patterns, products. Note: Be sure to pick up the guide that includes a layout map at the entrance to chart your own course. Hours are Saturday, 9 a.m. to 5 p.m.; Sunday, 9 a.m. to 3 p.m. Admission is $7; free for children 12 and younger. Accessible for strollers, wheelchairs and walkers, people of all ages. Food court; lounge with big-screen TV and a separate play area for children.

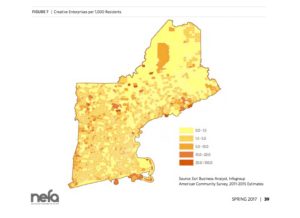

New England Foundation For The Arts report PDF. Produced for the NEFA by the Economic and Public Policy Research Group of the UMass Donahue Institute, June 2017.

Not a foliage report but data about creative enterprises and where they are located. Excerpt linked to NE Creative Jobs report.

“It includes many industry sectors and occupations that contribute to the economic vitality and cultural attractiveness of a place. Creative enterprises employ workers with all kinds of expertise, and creative economy workers are employed in nearly every sector that powers New England, from the arts, to education, to technology and science, to major global brands. They create what we listen to, watch, read, wear and buy. And they play a key role in determining where we want to live, work, and go on vacation…

“There are 156,260 workers in creative occupations at New England’s employers, some of whom are also counted in creative enterprise employment. These occupations only include workers that are performing work of great enough ongoing need to be hired and put on the payroll of New England’s businesses. Creative occupations in New England are 2.2 percent of all payroll occupations compared with 2 percent nationally, reinforcing the finding that creative work is a more prominent piece of the economic picture in New England than the U.S. as a whole. The region’s top payroll occupations are public relations specialists, librarians, and graphic designers. The artist subset of creative workers is also more concentrated in New England. Census data suggests that artists are 20 percent more prevalent in the region’s employment base than the nation’s.”

For those curious, ask questions, meet the people and vendors at the event. Some have a stand-alone business, others juggle many roles – but have a drive to create beautiful items, art, wearable warm textiles and useful items for the home. Since there is a correlation between making things known as crafts – and mathematical processes used for computing or in business, the replies to your queries may be surprising. (We've met engineers, inventors, patent holders, living history enthusiasts, archivists, historians, shop owners, teachers, RNs, business executives.)

Co-produced by ESE and the New England Sheep & Wool Growers Association, the indoor Fiber Festival of New England also offers workshops and the opportunity to meet live animals from llamas, alpacas and sheep to angora rabbits and fiber-producing goats – the people who care for them and know them. Ask questions; exhibitors will share their knowledge.

Workshops linked here on spinning, knitting, felting, tatting, punch needle, Tunisian crochet, rug hooking and more will be held both days. Note: Any materials fee needs to be paid to the instructor at the beginning of the workshop. Please be sure to check in 15 minutes before the start of a class.

Sheep shearing demos will also take place throughout the weekend; for times, here is the link to all events.

“Draw the art you want to see, start the business you want to run, play the music you want to hear, write the books you want to read, build the products you want to use – do the work you want to see done.” ― Austin Kleon