Time Bridge: Dutch Point, Pequot Heads, Rivers Large And Small

Rivers. Little River (aka Park River) flows to the great tidal river. Underground now, but it wasn't always that way.

An image is a portal to a moment in time. Details captured, sparks that lead to understanding more. Peel back time, like a clouded glass that gets clearer with each layer of information found.

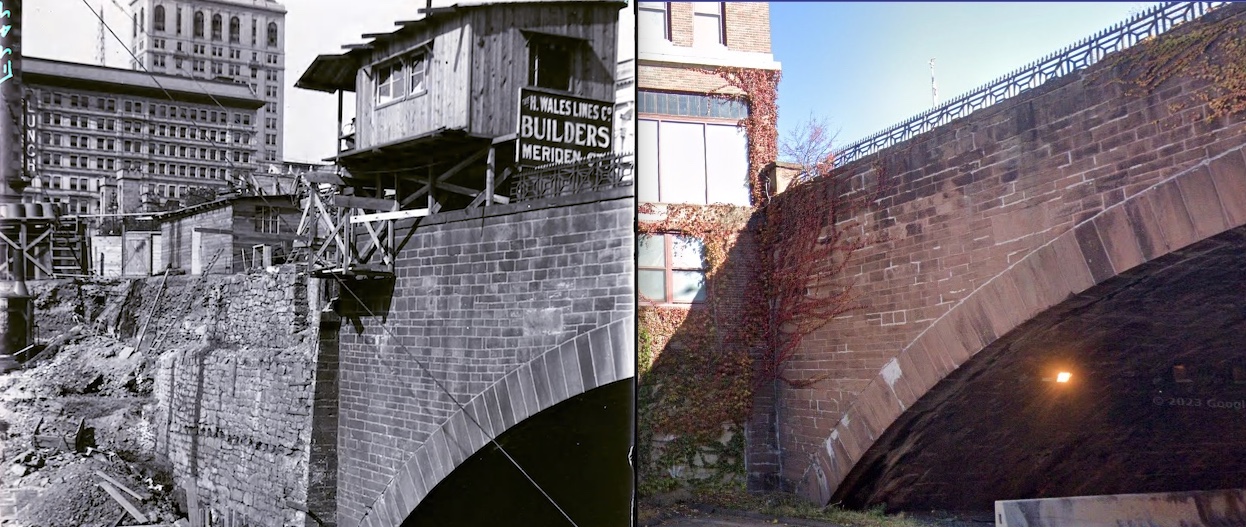

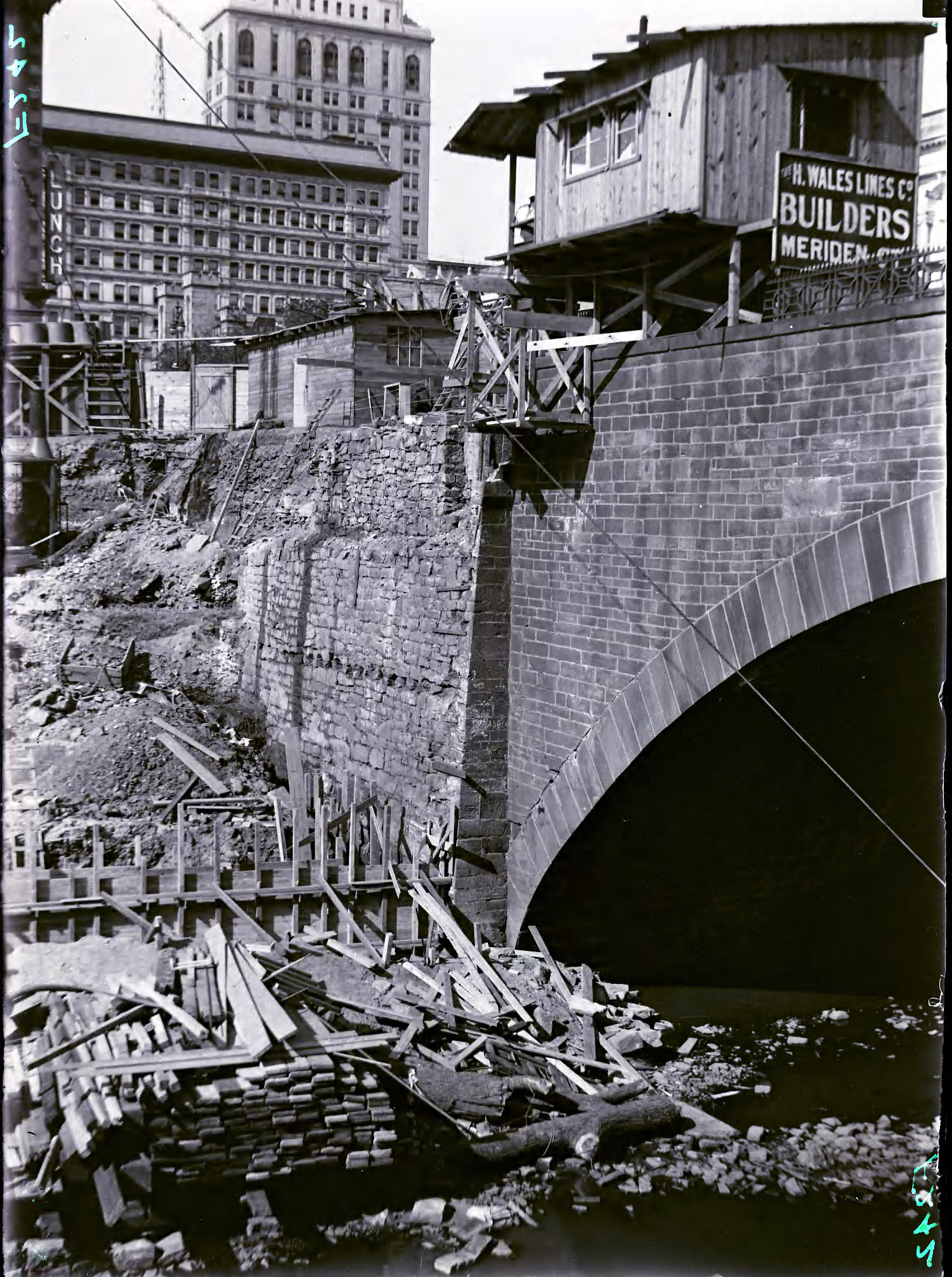

Note: For more about H. Wales Lines Co. and architecture, Ben Kennard, a recent story: https://www.moodogpress.com/2024/05/ben-kennards-house-his-horses-story-time-for-marph/.

View of construction underway on a bridge over the Park River, Hartford. A shed can be seen on the bridge. A sign beside it reads “H. WALES LINES Co./BUILDERS/MERIDEN CT.”

Genre

photographs

Organizations

Creator (cre): City of Hartford

Subject

Bridges

Geographic Subject

Park River (Conn.) Hartford (Conn.)

Extent

Source extent: 1 photograph : glass negative ; plate 4 x 6 in.

Held By

Hartford History Center, Hartford Public Library.

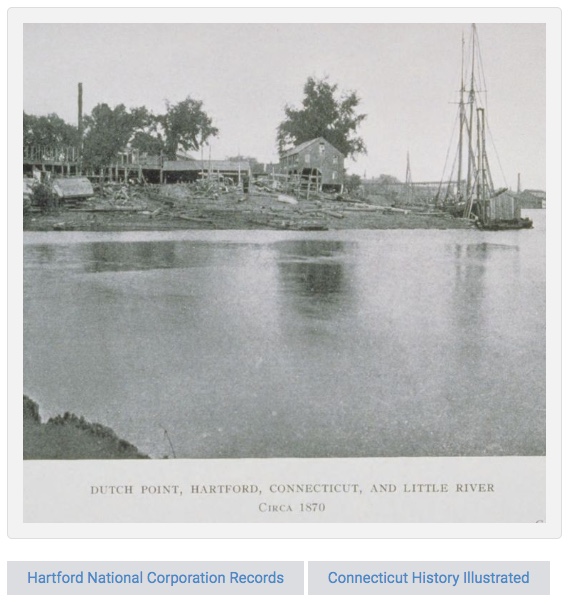

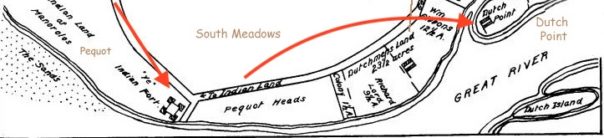

Searching for a copy of Colonial Hartford: Gathered from the Original Records by William DeLoss Love, led to frustration. Not available; no libraries (online search, two systems) had a copy to loan. But. Due to the wonders of digitization, access online. “Dutch Point. <- To Indian land. Hartford settlement 1635, the "Great River" aka Connecticut River. Map detail by William DeLoss Love, 1851-1918. Digitizing sponsor MSN. Contributor University of California Libraries." (Love libraries and knowledge combined with technologies. The online text is searchable and provides tabs to pages by keyword for research. Remote access to build and learn.) "... since known as 'Dutch Point.' This low land was directly east of the House of Hope. The northern boundary of the Dutchmen's claim, therefore, was the Little River, and a line projected eastward from its bend across to the Connecticut River. The original conveyance, from the Indians to the founders of Hartford, has long since disappeared."

And this, from page 90: “A roadway that ran from the House of Hope to the Indian fort, was its boundary on the southwest. The lots into which this tract was divided, are designated in deeds as lying at a place called ‘Pequot Heads.' It was an Indian custom, after their victories, to tie the scalps of their enemies to the tops of poles set up in a conspicuous place near their village, as a defiance and warning. Each great chief had a pole, which proclaimed his prowess. Sometimes the English were as barbarous in setting the heads of Indians on poles. We conjecture that it was the practice of this custom by the Indians that gave this tract its name, which it received at an early date. It was admirably suited to the purpose, being in full view of all who went and came on the river.

Context, Great River is Connecticut River. Red arrows have been added. Another story linked to this image.

The Encyclopedia of Connecticut: A Volume of Encyclopedia of the United States lists the following Native American groups (Indians) found in Connecticut: Nipmunks. Sequin or “River Indians” which included the following tribes: Tunxis. Poquonnuc. Podunk. Wangunk. Machimoodus. Hammonasset. Menunkatucks. Quinnipiac. Matabesec or Wappinger Confederacy which included the following tribes: Pootatuck. Weawaug. Unocwa. Siwanoy. Pequot-Mohegan. (There's more. Connecticut State Library site is linked here.)

A portal to get glimpses of a wilderness, home to indigenous humanity. What did any of this look like to those aboard a vessel in the river. (Because the views from the shore not recorded; at least none found. Yet.)

“As Sequassen's tribe never had an opportunity to make such a collection of bloody trophies, except in the Pequot War, it seems probable and natural enough that, when he removed immediately afterwards to the South Meadow, he should dedicate this river's bank to that purpose. So these scalps dangled from their poles in the breezes for many a day. This incident led the English to name the tract ‘Pequot Heads.' It is now in part the land along the Connecticut River, given to the City of Hartford by Mrs. Elizabeth Colt.”

Yes, indeed. Human history in layers, complex and colorful as filtered by writers and observers through time. Best to have three versions of the same point in time and to read many accounts; fascinating. (Related story with this portion, linked here.)

It's been two years since the eye-opening ride on the Onrust viewing the Connecticut River and learning about crossings, history, voyages. Before the pandemic. Thinking back, looking forward. More of learning the why behind place names once taken for granted.

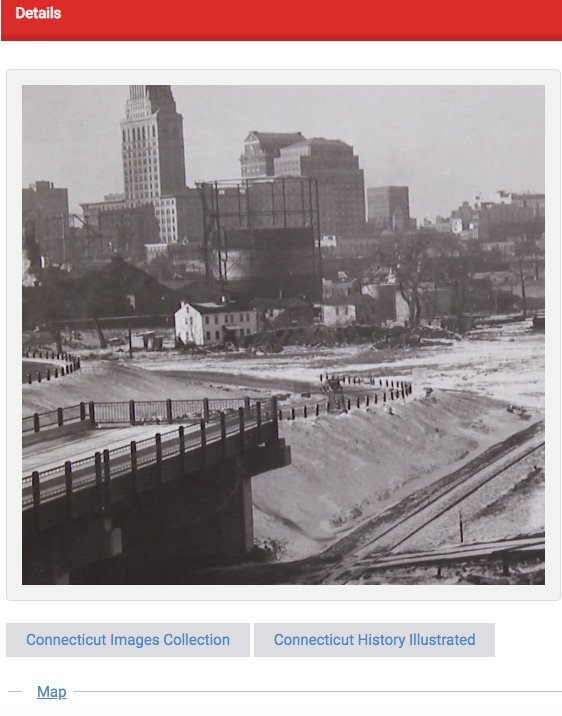

Sculpting the riverfront landscape for highways. Connecticut Digital Archive. Image is linked to collection, more views.

Into the unknown. No safety net, no depth soundings nor harbor markers for navigation. What would it take to explore rivers and land in 1614, when the continent was wilderness, yet populated by indigenous people — with fish and game a-plenty.

Connecticut River from its source near the Canadian border to Long Island Sound is the focus of the Connecticut River Museum in Essex, right on the riverfront. But a journey aboard the Onrust, an authentic reproduction of Dutch explorer Adriaen Block's vessel of exploration, gives the opportunity to see the living river and feel the power of wind and sails. (Related: Adriaen's Landing along the Connecticut River in Hartford, includes the Connecticut Convention Center, The Connecticut Science Center, Front Street, businesses, more.)

Onboard the Onrust (Dutch for “restless”), a 53-foot replica of Adriaen Block's ship (yes, it has diesel engines added), add imagination and set sail to find out. Stretches of the Connecticut River still look like what Block and his crew must have seen as they explored and mapped the region. All hands on deck for this journey: Dan Thompson, captain, fiddle player, amateur historian. Jim Byron, deckhand, retired from his own custom sewing business to go sailing. Beth Avery, deckhand, historic interpreter and role player (she has also portrayed Mark Twain's wife, Olivia, at the Mark Twain House & Museum in Hartford) and the official “powder monkey” on board (fetches black powder for cannons). As the crew deftly handles the ship, guests can sit, stand, ask questions, enjoy the views. The sound of ropes and pulleys, wind and sails, inspiring. River bluffs slip by, geological forces on display that few get to see unless on the river.

The original Onrust was built near Manhattan during the winter of 1614, according to the Connecticut River Museum brochure about the vessel, which takes visitors out onto the river (and is available for charter). Block and crew sailed the New York coast and rivers, Long Island Sound and harbors and Connecticut's coast, discovering (for Europeans) the Housatonic and Thames Rivers, then up the Connecticut past what would become the city of Hartford.

Wind, weather, currents to read. Stars and sky. Sandbars, underwater snags. Storms and channels. Just think about it. On deck, ever watchful. Below deck, sleep, eat, stay warm in the cold; sweat when it is hot and there is no breeze. Biting insects. Close quarters. Well, there's always water — salt, brackish, river — when the ship drops anchor. Bathing.

The motivation to risk all. Trade. Pelts. Markets. Perceived and real riches.

From the portrait inside the museum: “The Master Mariner. Adriaen Block was 47 years old and an experienced mariner when he sailed through Hell's Gate and into Long Island Sound. He navigated the Connecticut River as far north as Enfield Rapids and his journal of that voyage has specific observations on the River's depths, its navigation and on the Native Americans. He was gathering information for Amsterdam merchants on the potential of the fur trade and had made at least two previous voyages to the New World. This contemporary painting by Jim DeCesare illustrates Block on board the small yacht Onrust.”

Hello. The Onrust (and Adriaen Block) in the Connecticut River, from a multi-storied mural at the Connecticut River Museum in Essex. Russell Buckingham is the artist. He also created the “British Raid on Essex” mural, the “Turtle” backdrop mural, and the “Comeback River” Mural on the second-floor exhibit.

Memories thread seeing a larger picture of the river, rivers. A voyage taken from dock of the Connecticut River Museum started with melodious welcome on a conch by Daniel C. Thompson. The shell is the Onrust’s “kinkhoorn.”

Conversations with travelers from Ohio, who found their day excursion to Essex (lunch at The Griswold Inn and a tour of the museum before boarding the Onrust for the river tour) by going online and searching “things to do within so many miles of Hartford” and choosing between results for that search. Pre-pandemic.

Time passes quickly on the river between all there is to see and lively conversation. Bald eagles, cormorants, islands, sightings of sailing school classes on the water, a house on an island available to rent. A former tavern, ferry crossings no longer there. History, stories, and friendly waves from other boaters as they pass and take images of the Onrust in full sail.

All too soon it was time to return to the dock at the Connecticut River Museum and Essex, with a bevy of boats, slips, history in layers.

Note: For more information about the river, cruises, call (860) 767-8269, Connecticut River Museum is host for the Onrust.

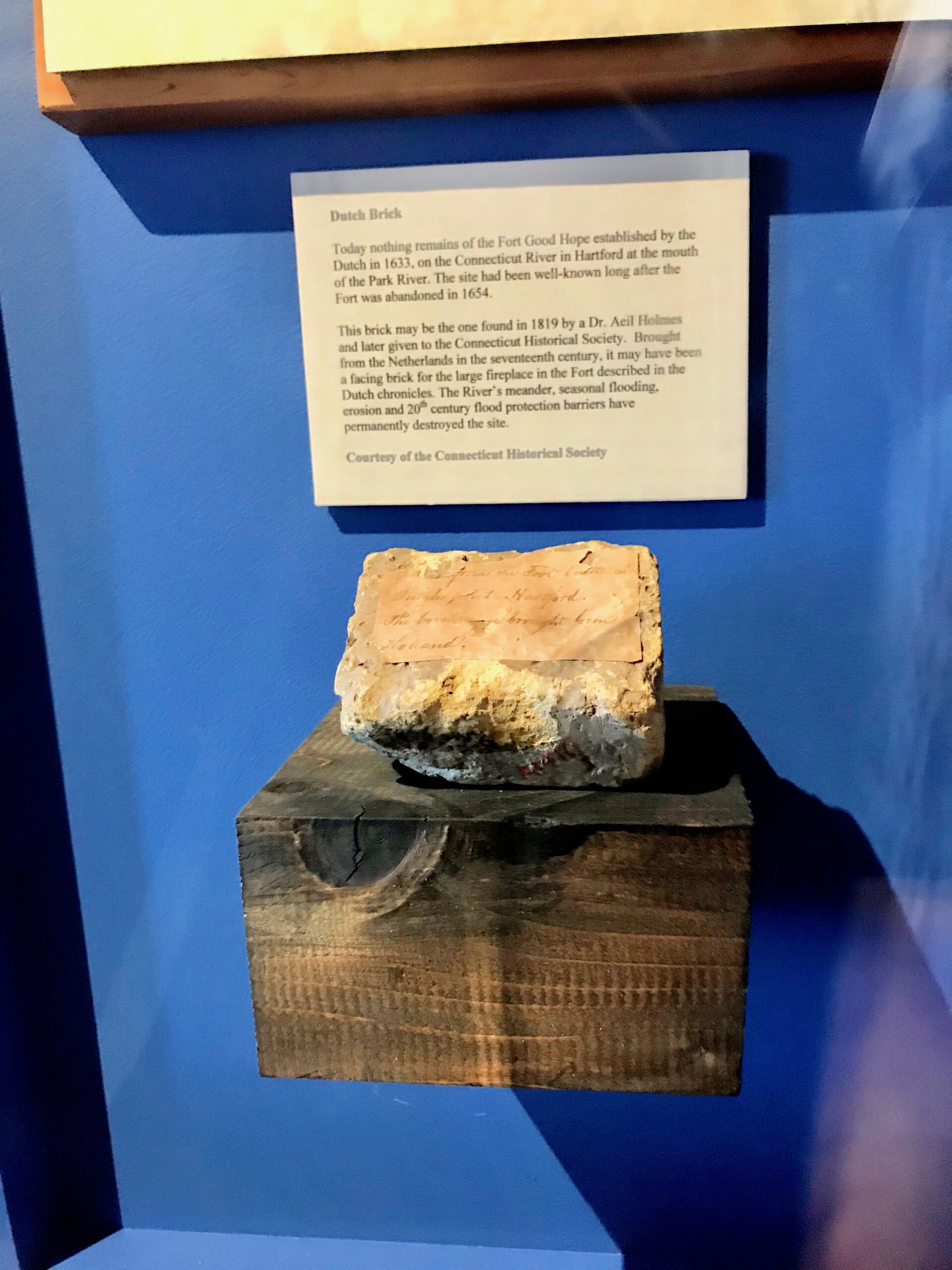

Postscript: Research about Dutch Point in Hartford leads to additional explorations with insight gleaned from a day with the Onrust, thoughts of what was then-wilderness and looking over Connecticut River Museum's exhibits. A brick. “Today nothing remains of the Fort Good Hope established by the Dutch in 1633, on the Connecticut River in Hartford at the mouth of the Park River. The site had been well-known long after the Fort was abandoned in 1654…”

Note: A portion of this story was originally published Aug. 1, 2019. Curiosity, lead on. Archives, walks, readings, place names, interviews all provide parts of a puzzle. Next up, Baileyville. A story that appeared decades ago only in print gets a new (digital) chapter.