Of Technology, Land Use, Birds, Honey Bees, Other Natural Wonders: Think Ahead

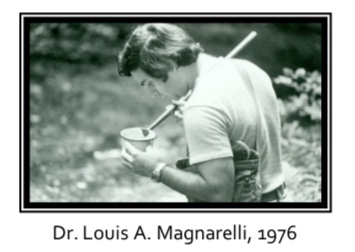

For those who may have missed it (and we miss him), worth noting: The Connecticut Agricultural Experiment Station Research Foundation, Inc. and the Board of Control of The Connecticut Agricultural Experiment Station announced the establishment of the Louis A. Magnarelli Memorial Fund, to commemorate the life and work of Dr. Louis A. Magnarelli. Throughout his career at The Connecticut Agricultural Experiment Station (CAES), Dr. Magnarelli maintained his unwavering commitment to the station’s motto ‘Putting science to work for society' and it was an honor and privilege to interview him and share his deep knowledge of science. He was always patient and welcomed questions.  The Louis A. Magarelli Memorial Fund (PDF) is linked here. “Dr. Magnarelli joined the Experiment Station in July 1975 and started his career in a laboratory in Jenkins Building. Over the years, his research expanded, with collaborators at the Station and throughout the U.S. His work on ticks, tick-associated diseases, and serological testing for vector-borne pathogens, in addition to his many other accomplishments are recognized internationally. Through the course of a career that spanned four decades, he published over 218 scientific articles. Dr. Magnarelli served as Chief Entomologist and State Entomologist from 1987-2004, Vice Director from 1992-2004, and was appointed the Station’s eighth Director in 2004. Regulatory responsibilities came with these positions, which required that Dr. Magnarelli establish and enforce 1976 quarantines to protect Connecticut. He fully recognized the economic impacts these decisions had on citizens and always listened intently to those who voiced their concerns at hearings. During his career, he oversaw quarantines on many insect pests, plant pests, and plant pathogens. He capably juggled administrative responsibilities with his research. Drs. Waggoner, Magnarelli, and Anderson at the Jenkins-Waggoner Laboratory renovation groundbreaking 2013 The Louis A. Magnarelli Memorial Fund will be used by the Station’s Board of Control to create a physical memorial on the New Haven campus to honor Dr. Magnarelli and to support the Board of Control’s Louis A. Magnarelli Post-Doctoral Research Fellowship program.”

The Louis A. Magarelli Memorial Fund (PDF) is linked here. “Dr. Magnarelli joined the Experiment Station in July 1975 and started his career in a laboratory in Jenkins Building. Over the years, his research expanded, with collaborators at the Station and throughout the U.S. His work on ticks, tick-associated diseases, and serological testing for vector-borne pathogens, in addition to his many other accomplishments are recognized internationally. Through the course of a career that spanned four decades, he published over 218 scientific articles. Dr. Magnarelli served as Chief Entomologist and State Entomologist from 1987-2004, Vice Director from 1992-2004, and was appointed the Station’s eighth Director in 2004. Regulatory responsibilities came with these positions, which required that Dr. Magnarelli establish and enforce 1976 quarantines to protect Connecticut. He fully recognized the economic impacts these decisions had on citizens and always listened intently to those who voiced their concerns at hearings. During his career, he oversaw quarantines on many insect pests, plant pests, and plant pathogens. He capably juggled administrative responsibilities with his research. Drs. Waggoner, Magnarelli, and Anderson at the Jenkins-Waggoner Laboratory renovation groundbreaking 2013 The Louis A. Magnarelli Memorial Fund will be used by the Station’s Board of Control to create a physical memorial on the New Haven campus to honor Dr. Magnarelli and to support the Board of Control’s Louis A. Magnarelli Post-Doctoral Research Fellowship program.”

Leading by example as a human — parent, teacher, citizen — is a great responsibility; lessons learned remain when people are gone.

An February unfolds, thoughts turn to growing season ahead, life in all forms, time. Daylight hours increase, but there still is much winter and cold in reserve for the region. Dogs, horses, books. Birds. Reading, writing. Learning by doing. Wood to haul, fences to walk; repairs and maintenance. Listening. Great horned owls once nested in a beloved hollow old maple, but a new owner of that property on which it grows cemented up the nest site. Those soulful calls are no longer heard. The well-intentioned man did put up a bird box which is occupied in spring by sparrows. But he was not aware of the (spectacular) owls which had previously returned to the same tree each January for more than a decade.

My father once told of his seeing a large bird on a fence post in a big pasture/hayfield while he was a young man out hunting rabbits to put food on the table, circa 1930. This was prior to his going to a Civilian Conservation Camp (CCC) in Colorado Springs to work and send his paycheck home, but after the death of his mother, which left my grandfather with four young children to raise, alone. (So, a single parent way ahead of his time (and not by choice), my gramp succeeded in holding his family together, two boys, two girls. Part of the cost was that his oldest daughter, who loved to learn, had to leave school and her childhood behind to cook, clean, and do much to raise her siblings.)

Decades later, my father described that he shot the bird without thinking it through, and when he walked over discovered an owl. Deep regret for taking the life of something so beautiful stayed with him; that pain was communicated in his voice many decades later, after his service in the U.S. Army in World War II (South Pacific), then returning home to work and to meet the woman who became my mother, build a home, have children. He said his action to bring down that owl without first identifying it was stupid; but nothing would bring life back. The story was told as a warning and as a form of penance; he instilled a deep reverence for nature and helping things grow in his offspring.

Curiosity can lead to many positive places if tempered by discipline and led by patience. Combine New England and New York, a region that features a profusion of nature centers, conservation areas, educational resources available connected with universities, colleges, communities, that are simply exceptional.

One such place where people gather to learn and think ahead is the White Memorial Conservation Center (WMCC) in Litchfield, Connecticut. The White Memorial Foundation (WMF) is the result of the vision of “two generous and creative people, Alain C. White and his sister, May W. White. Between 1908 and 1912 they purchased several tracts of land surrounding their family’s Whitehall property on the north shore of Bantam Lake.

“In 1913 these lands were conveyed to the White Memorial Foundation, an organization that was incorporated in May of that year as a memorial to Alain and May’s parents, John Jay and Louise. In 1964, the Trustees of The White Memorial Foundation established The White Memorial Conservation Center to further the Foundation’s education role through the implementation of natural history education and research programs for the public. Located in the heart of the Foundation property, the Conservation Center is housed in ‘Whitehall,' the former White family home. The center, whose mission is to instill understanding, appreciation and respect for the natural world, provides year-round programs for people of all ages. Programs are directed by full-time professional staff, assisted by a core of volunteers and part-time employees. The Center also operates a nature museum with exhibits focusing on the interpretation of local natural history, conservation and ecology. More than 20,000 people of all ages visit the center each year to walk through the museum or take part in an education program. The center is a 501(c)(3) not-for-profit organization; contributions made are tax deductible to the extent provided by law.”

Ice, mud, snow. Hail, sleet, rain. In the depths of winter, where does your food come from and how does it stay preserved? We all may not think about this too much in 2020 unless the power is down for any length of time, but the water resources in the region once provided the technology to keep food cold year round.

Yes, technology as defined by Merriam-Webster: “1a: the practical application of knowledge especially in a particular area…; b: a capability given by the practical application of knowledge (a car's fuel-saving technology); 2: a manner of accomplishing a task especially using technical processes, methods, or knowledge (new technologies for information storage); 3: the specialized aspects of a particular field of endeavor (educational technology).”

Cut It Out: The Local History and Practice of Ice Harvesting, Saturday, Feb. 8, 10 a.m. to 1 p.m., WMCC. Free; donations welcome to help defray the conservation center's programming expenses.

Learn more about ice harvested from Bantam Lake and how it was used, hear about the process and see tools used. The program culminates with “Cut Ups” Jeff Greenwood, James Fischer, and Gerri Griswold demonstrating how ice was cut and moved using the same tools and methods. In the event of thin or no ice, there will be a guided walk down the Lake Trail to visit the old icehouse ruins. The group will walk and stand on Ongley Pond for extended periods (weather permitting). Dress for the weather; wear warm and waterproof boots. Hot beverages and treats will be provided.

Full moon hike later in the day Saturday, Feb. 8. Join WMCC and Appalachian Mountain Club Member Steve Troop on a hike or ski or snowshoe ramble 6 to 8 p.m. along the Lake Trail, Butternut Brook Trail, and Windmill Hill Trail. Meet at Ceder Room and return after the outing to a warm fire. Bring a snack and something warm to drink. For information call Steve (860) 480-9926. Free. but donations welcome.

Of interest is the WMCC Gift Shop with products that include maple syrup from Brookview Sugar House in Morris, items handcrafted in the state. Music, books (local authors and naturalists), toys, gemstones, bat houses, WMF patches, much more.

Now for another long-range thinking-ahead knowledge gleaned from science.

The nursery industry sells more than $4.3 billion worth of ornamental plants in the U.S. each year, representing a tremendous investment in the appearance of human-managed landscapes, according to The Connecticut Agricultural Experiment Station (CAES).

Current concerns about the health of pollinators generally, and honey bees in particular, raise the question – are we helping honey bees with the flowering ornamental plants we choose? Beekeepers have honey bee hives in a range of suburban, urban, and rural environments, and honey bees in mostly managed landscapes could be using the flowering plants we choose as a source of food.

Red maple flowers. Early food for bees and pollinators; the blossoms have a delicious fragrance. TW/MDP

Scientists from CAES, in collaboration with researchers from the Center for Pollinator Research at Penn State University, York University in Toronto, Canada, and the University of Maine, recently addressed that question in a survey of pollen collected by honey bees in three commercial ornamental nurseries.

Pollen is the source of protein, fats and many minerals for honey bee colonies, with nectar serving the primary source of sugars for energy and honey production. The pollen was collected from the honey bee colonies at three commercial ornamental plant nurseries in Connecticut using a pollen trap, which removes the pollen from the pollen baskets on the legs of honey bee workers as they return to the hive.

The plants from which the honey bees collected pollen were identified using two techniques: palynology, the identification of pollen grains using microscopic structures; and DNA metabarcoding, matching genes extracted from the pollen to DNA sequences for the same genes from plants.

Honey bees at the nurseries collected pollen from a very diverse mixture of plants, with 203 genera identified by either or both of the two methods. Five of the most commonly detected genera, Rosa, Hydrangea, Solidago (goldenrod), Spiraea, and Viburnum were grown in the nurseries, although they also include species that grow wild in the area. Other most commonly found genera were plants often considered to be weeds – Trifolium (clover), Plantago (plantain), and Ambrosia (ragweed) – or crop plants like Zea (corn). One unexpected genus was Nymphaea (water lily), which suggests that honey bees are looking at our pond plants for pollen more than we realized.

Dr. Kimberly Stoner, senior author of the study, said, “Perhaps the lesson to be learned is that honey bees have a much wider range of flowers they enjoy than we humans do! They can benefit from the flowering ornamentals we plant and from our weeds, too.”

Another aspect of the study was to compare the two methods of pollen identification. Neither method was clearly superior – each found some plant genera that the other missed. DNA metabarcoding is still a new method of pollen identification, and further work is needed before it will be able to replace palynology.

This study was funded by the Connecticut Department of Energy and Environmental Protection, with additional funding from the Specialty Crops Research Initiative of the National Institute for Food and Agriculture.

Journal Reference: Sponsler, D.B., C. M. Grozinger, R. T. Richardson, A. Nurse, D. Brough, H. M. Patch, and K.A. Stoner. 2020. A screening-level assessment of the pollinator-attractiveness of ornamental nursery stock using a honey bee foraging assay. Scientific Reports. https://doi.org/101038/s41598-020-57858-2.

This paper is freely available online at www.nature.com/articles/s41598-020-57858-2.

——————

For gardeners with a deep love and appreciation for the land and how all forms of life are intertwined, what appears to be a weed to some is a valued herb with many applications. (Invasive bittersweet is a notable exception.)

The love of gardening is a seed that once sown never dies, but always grows and grows to an enduring and ever-increasing source of happiness.

The New England Unit of The Herb Society of America is the founding unit of The Herb Society of America. From the official site: “In 1933, seven women formed an educational society dedicated to the study and use of herbs. The Society has grown from one unit to 45, and from the initial seven members to approximately 2,300 members in the United States, Canada and other countries. The New England Unit has about 50 members, living mostly in Massachusetts.

“The New England Unit maintains a Teaching Herb Garden at the Gardens at Elm Bank, home of the Massachusetts Horticultural Society in Wellesley, Mass. Please come and visit the gardens next summer. Meanwhile, please enjoy a Summer Garden 2019 slide show.

The annual herb plant sale at Elm Bank in Wellesley, Mass., is Saturday, May 9, 2020 in conjunction with Mass Hort's Gardeners' Fair.

The Herb Society of America is dedicated to “promoting the knowledge, use and delight of herbs through educational programs, research and sharing the experience of its members with the community.” For information, (440) 256-0514; www.herbsociety.org.

Note: The book Birding in Connecticut by Frank Gallo, published by Wesleyan University Press/Garnet Books (2018) is so exceptional, this go-to volume with maps and illustrations was to be featured here but will instead be reviewed in our next story. The author dedicates his book, thus: “…to my mother, Eileen, who started me on my journey and has been there with me through it all. All my love.

“And to the memory of my mentors and friends now gone, Ed Shove, fearless leader of the Lighthouse Hawk Watch; Noble Proctor; Sal Masotta; George and Millie Letis; Richard Haley; Mark Hoffman; and Lee Aimsbury. And to Marion Aimsbury, who happily, is still with us. Thank you all.”