Moonshine. Mountain Dew. White Lightnin’

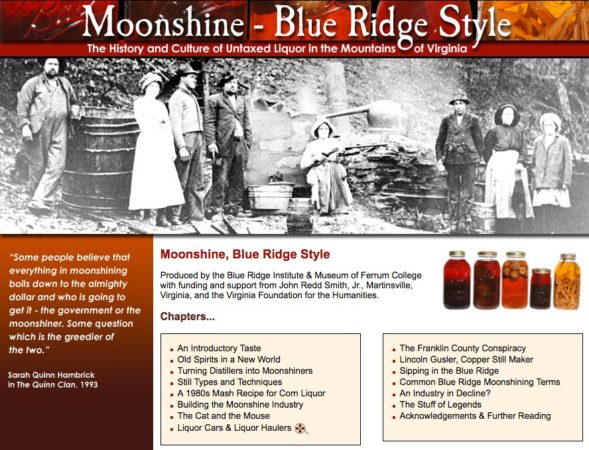

Moonshine. The stuff is legendary. Now there is a comprehensive exhibit and archive about it online, part of the Blue Ridge Institute & Museum (BRI) at Ferrum College in southwestern Virginia, located in a county that has long called itself “The Moonshine Capitol of the World.”

“The institute documents and showcases folk traditions of the region, and it was only natural for us to do an exhibition on Blue Ridge moonshining in our museum galleries,” according to Vaughan Webb, director, Institutional Research at Ferrum College.

This story in words and images is one labor of love not to be missed. By the way, BRI features changing exhibits plus hosts the annual Blue Ridge Folklife Festival (always the fourth Saturday in October).

“The center received a grant from the Virginia Foundation for the Humanities to help support the gallery exhibition. The trouble with gallery exhibitions is that once they are dismantled, much of the information in them can be forgotten.”

Then Lisa Bowling, director of development at Ferrum College, who knew that John Redd Smith, Jr., had crossed paths with moonshiners many times in his life and had enjoyed the gallery exhibition asked Mr. Smith if he would sponsor the online exhibition. He agreed.

Smith is the son of a Martinsville Virginia Commonwealth's Attorney, John Redd Smith who was Commonwealth Attorney for Henry County from 1900 to 1912. During the time mentioned, he defended moonshiners and was a well-known defense attorney. He knows well the people, tales, and temptations surrounding Franklin County's most famous beverage. Once joking he said “I never knew that liquor came in anything but a Mason jar until I was grown because bootleggers would pay my father in homemade brandy.”

Smith is the son of a Martinsville Virginia Commonwealth's Attorney, John Redd Smith who was Commonwealth Attorney for Henry County from 1900 to 1912. During the time mentioned, he defended moonshiners and was a well-known defense attorney. He knows well the people, tales, and temptations surrounding Franklin County's most famous beverage. Once joking he said “I never knew that liquor came in anything but a Mason jar until I was grown because bootleggers would pay my father in homemade brandy.”

The exhibit sheds light on many myths as well as allowing access into the risks and rewards of the trade, including the brillance of inventive mechanics.

After all, moonshining involves a host of customs, including farming, foodways, coppersmithing, woodworking, automobile engine building, and superstitions. It's been called ‘the second oldest profession in the world.'

From the exhibit story:

“In the era prior to police two-way radios, a hauler could possibly outrun officers with a fast vehicle. Some of the resulting chases are the stuff of Blue Ridge legend. Officers at times did shoot at the tires of their prey, and revenuers and liquor haulers alike suffered car crashes. If the hauler was spotted, he might lose his pursuer on dark country roads. Some skilled drivers perfected the “bootleg turn,” a technique of spinning 180 degrees in a quick skid.

A comprehensive and rich collection of stories, photos, first-hand accounts and videos is linked to this image of Moonshine, Blue Ridge Style online at the Blue Ridge Institute.

“With the flick of a special switch, a hauler could turn off his taillights, and occasionally vehicles were fitted with bright rear-facing lights to blind pursuing revenuers. If the hauler could not shake the agents, he might jump out the car and run on foot into the woods, avoiding arrest but losing both the vehicle and the liquor.

“Haulers had no desire to draw attention to themselves by speeding or driving a conspicuous vehicle. Special springs and shocks were installed on cars and trucks to hold the vehicles level when loaded. At times drivers switched license plates to avoid identification. Packed with up to 132 gallons of whiskey, the 1940 Ford coupe was the “runner’s” vehicle of choice into the 1950s. Since the 1970s haulers have switched to vans or pickup trucks with camper shells.

Stacked nearly flush with the truck bed, the half load of liquor pictured here weighed over a 1,000 pounds, even in light plastic jugs. Franklin County, Virginia, 1979, courtesy of Ferrum College.

“Much has been made in popular culture of the connection between liquor haulers and NASCAR auto racing, but in truth few Blue Ridge moonshine drivers dabbled in organized racing. The real ties between the two activities took place in local garages where mechanics modified engines for speed and suspensions for handling. The mechanic’s skills were useful to both stock car racers and moonshine runners.”

Modifications such as suspension enhancements – extra leaf springs shown here on a 1951 Ford pickup truck, held vehicles level even when carrying a full load of whiskey. This particular truck was used to haul moonshine out of Franklin County, Virginia, for many years. Image is courtesy of BRI and linked to page with many fascinating details and stories.

Today there is hardly anyone in the moonshine business. When the economy boomed after World War II, the wiser men who had been in trade took jobs in the furniture factories and textile mills – jobs offered retirement plans and insurance. Federal agents now use the RICO Act laws, originally created for use against the Mafia, to charge everyone involved in a moonshine operation with racketeering.

“Fruit liquor” (four jars on the left) is made by filling a jar with fruit

and then adding sugar and moonshine. Medicinal “bitters” (right)

can include a variety of herbs, barks, and spices. BRI image, connected to the online exhibit.

“Moonshining is an intriguing topic, and just about everyone we approached about the exhibition generously shared what they knew or owned,” Webb notes. “Of course, we're still collecting.”

Editor's Note: Our thanks to J. Vaughan Webb, assistant director, Blue Ridge Institute & Museum, Ferrum College. All images are courtesy of BRI archives collection and are used by permission. For more about exhibits, folklife events or the farm museum collections, visit www.blueridgeinstitute.org.

Addendum: Tripp Smith of Virginia pointed out there is an error in the story as follows: “The text in the article that describes John Redd Smith's father as being Commonwealth Attorney needs to be corrected. John Redd Smith was Commonwealth Attorney for Henry County from 1900 to 1912. However, he did not prosecute moonshiners during the time mentioned. He defended them and was a well-known defense attorney. It can be said that my father did not know that distilled spirits came in containers other than Mason jars until he went off to war, in 1943 but my grandfather was NOT prosecuting liquor cases except had it been during the period from 1900 to 1912.”

Our appreciation for Tripp Smith's input for setting the record straight.