Rivers of Time: Land Trust Walk, River and Stanton-Davis Homestead

Editor's note: This story was originally published in July 2018. An open house in September 2019 will give visitors the opportunity to see a place where stories of three cultures converge and communications prove a key element. Never more relevant. Indigenous place names abound in the region and across the continent. Also, the story of Venture Smith is really quite amazing.

River time. A walk leads to ideas and stories that percolate as the mind enjoys water, earth, sky. Seeking a remembered sign near a boatyard, the recollection of another July expedition sparked connections.

Gifts of a day on a guided walk because of a social media post by The Stonington Land Trust (SLT), which has the stewardship of a combined “495.40-acres of land in the Anguilla Brook and Pawcatuck River watersheds.” The walk began on SLT's Osbrook Preserve, which abuts the Davis Farm, featured a Native American site shared by both properties and wounds along to the Cove, on the Pawcatuck River. Neighbors.

The glimpse of what looked like a writer's cabin in the woods not far from the road – and then an osprey perched at the edge of the woods near the marsh on the way out. Best of all – to see the former home of the late Whit Davis and his family on the way to and from the walk. Knowing so many lives intersect there and on the surrounding land, a place that features stories woven into the very fabric of the state and so important to the nation. (An interview with Mr. Davis — a privilege — linked here.)

The Stanton-Davis Homestead Museum, Inc. (SDHM, Inc.) is a non-profit 501-c-3 corporation, neighbor to the land trust holdings. It was formed to restore and preserve the oldest home in Stonington, Connecticut, built by Thomas Stanton circa 1670. Its mission is to “protect, maintain and preserve the Stanton-Davis Homestead and artifacts, for the purpose of creating a public museum and living educational center, open to the public, which is dedicated to the memory of Thomas Stanton, Mohegans, Pequots and African Americans associated with the history of the homestead, all of whom were instrumental in the founding of Connecticut.”

The Stanton-Davis Homestead will host an open house on Sunday, Sept. 22, 2019. Visit the homestead, learn some of the rich history of this house.

The Stonington Land Trust Walk and some conversation. The Jeep was on site for anyone who needed a ride back.

So when that small still voice is insistent and speaks loudly, listen – then follow. Go exploring. Learn something new, don't wonder what if. Where ideas will lead, only time will tell.

For instance, a walk (2018) led by Dr. Nicholas F. Bellantoni, Emeritus State Archaeologist, University of Connecticut Emeritus Professor of Anthropology, hosted by the Stonington Land Trust.

“Go and find out.”

The opportunity to walk land now preserved and listen to Dr. Bellantoni's experiences and findings, to “see” what happened here by his reading of the landscape and archaeological excavations.

A drive down an ever-narrowing road led to a small tent over a registration area and the courteous land trust members – and a path to join the walk. (Bug spray, boots and precautions against ticks? Yes. Some along on the walk wisely wore long pants tucked into boots; hats and neck protection.)

Bellantoni is a master storyteller, bringing the past to life in a lively conversational style – he spoke about shell middens and people whose lives connected here – past and present. Of the late Whit Davis and his father. Of farmer's fields and stone points and collected artifacts. Of Norris Bull of West Hartford (later, Old Lyme) and his digging and buying collections of artifacts in the 1930s. (More about this in the Norris Bull Anthropological Collection of the Connecticut Archaeology Center.)

What was found by scientific research since – and what that revealed about diets, food consumed. That food connects us all – even across time. Oysters and rivers, staying active. Of summer breezes and sharing stories.

With scenic views as a backdrop, he spoke of information preserved by the chemical composition of the shells – down to fish scales. It's small wonder that humans centuries ago picked a wide flat rock (not seen due to the overgrowth, but described) for enjoying oysters freshly harvested in this same spot near the Pawcatuck River. Subtract the trees and imagine the plants and brush gone – this frontage on the river is simply spectacular. On the return to the starting point, meeting Bertrand F. Bell III to walk alongside and listen to his career(s), business and the life journey that led him to Connecticut, wonderful. (More about Peaceable Kingdom Antiques in another segment.)

Onward to the book.

“These stories resided inside me and simply had to come out.”

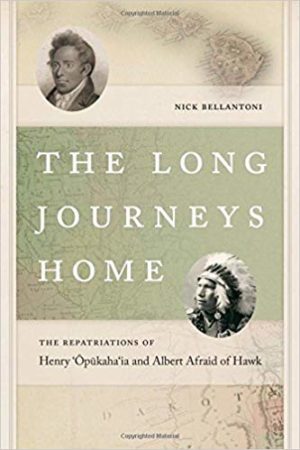

– Nick Bellantoni from the acknowledgments for his new book (published Sept. 4, 2018) “The Long Journeys Home: The Repatriations of Henry ‘Ōpūkaha'ia and Albert Afraid of Hawk” (The Driftless Connecticut Series & Garnet Books/Wesleyan University Press).

From the Amazon description of the book:

“Henry ‘Ōpūkaha'ia (ca. 1792–1818), Native Hawaiian, and Itankusun Wanbli (ca. 1879–1900), Oglala Lakota, lived almost a century apart. Yet the cultural circumstances that led them to leave their homelands and eventually die in Connecticut have striking similarities.'Ōpūkaha'ia was orphaned during the turmoil caused in part by Kamehameha’s wars in Hawai’i and found passage on a ship to New England, where he was introduced and converted to Christianity, becoming the inspiration behind the first Christian missions to Hawai’i. Itankusun Wanbli, Christianized as Albert Afraid of Hawk, performed in Buffalo Bill’s ‘Wild West' as a way to make a living after his traditional means of sustenance were impacted by American expansionism. Both young men died while on their ‘journeys' to find fulfillment and both were buried in Connecticut cemeteries. In 1992 and 2008, descendant women had callings that their ancestors ‘wanted to come home' and began the repatriation process of their physical remains. CT state archaeologist (emeritus) Nick Bellantoni oversaw the archaeological disinterment, forensic identifications and return of their skeletal remains back to their Native communities and families.

The Long Journeys Home chronicles these important stories as examples of the wide-reaching impact of American imperialism and colonialism on indigenous Hawaiian and Lakota traditions and their cultural resurgences, in which the repatriation of these young men have played significant roles. Bellantoni’s excavations, his interaction with two Native families and his participation in their repatriations have given him unique insights into the importance of heritage and family among contemporary Native communities and their common ground with archaeologists. His natural storytelling abilities allow him to share these meaningful stories with a larger general audience.”

Note: The name Henry ‘Ōpūkaha'ia has been updated for accuracy per the publisher to include the diacritics – from the original mention and spelling of the book mention on Amazon. To honor and respect a person, a name must be accurate and true. Thanks to Wesleyan University Press for this information.

Note for context: The Office of State Archaeology at the Connecticut State Museum of Natural History and the University of Connecticut have been involved since the mid-1980s in “the reburial and repatriation of Native American remains and artifacts with the state's Indian community. Objects removed during excavations for the construction of a home in Mystic, Conn., in 1942… were sold some time later by the property owner to Norris L. Bull, a collector of Indian artifacts from the 1930s to the 1950s. In 1963, Bull's estate provided for the University to receive these and other cultural items, and they were held by the Department of Anthropology until 1994, when they were accessioned by the State Museum of Natural History. … Based on geographic and historical evidence, the site of the burials coincides with the aboriginal territory of the Pequot Indians, and is close to the site of the Pequot Fort attacked by John Mason in 1637. Bellantoni says the attributes of the burial goods are consistent with a 17th-century date for the burials. Members of the Mashantucket Pequot Tribal Nation of Connecticut are the direct descendants of the Pequot Indians.” – UConn Advance (2002)

And, let's repeat, indigenous place names abound in Connecticut and Rhode Island, across the continent. More stories of place and time must come out.